I was spurred to write this when talking to Sampson the other day. He mentioned talking to a Crossfitter who told him that is how all athletes should train. I’ve read stuff like this from people, but it’s got to stop. So I’m going to do my damnedest to try.

You may or may not have heard of Crossfit, a training system that promises the optimal way to improve fitness. Along those lines, there is a lot of bitching going back and forth about Crossfit as a training modality for athletes.

A few disclaimers:

- If you are not a competitive athlete and want to “do” Crossfit, have at it. I think there are better ways to train, but do whatever you want. But if you’re an athlete, you are doing yourself a great disservice if this is your training model.

- Crossfit itself is nearly impossible to define. Any time I’ve seen someone bash Crossfit, someone will jump in to say “well that’s not what it is.” And ask any Crossfitter to define what it is, and you’ll get some amorphous definition that suits their needs at the moment. But as soon as you start shooting holes in it, it will change. But I’ll try.

- Fitness is task-dependent. Being “fit” for a task does not mean you are aerobically fit or you are OK at a bunch of stuff. Therefore, any broad definition of “fitness” that doesn’t include that caveat is fundamentally incorrect.

Now, on with the show…

What the heck is GPP?

The main reason Crossfitters tout the superiority of Crossfit for athletes is that it is “GPP.” They train “for the unknown.” For those who are unaware, GPP stands for General Physical Preparation. GPP is defined as:

“Exercises or activities NOT directly related to the sport, that develop physical qualities, improve technique, (or address individual morphological (structural) issues).”

- Mike Gattone- Adapted from A. Medvedev

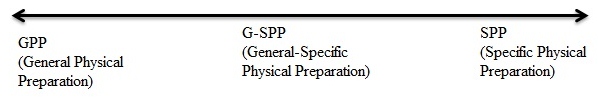

First and foremost, GPP does not mean “do a bunch of different sh” – ahem – “stuff.” Nor does it mean train every possible energy system and every possible movement. In the development of sporting prowess, there is a continuum of training means that looks something like this:

This does not mean that everything is rigidly categorized; rather this is simply to demonstrate the classification of means is a continuum, and no exercises can simply be classified as “general” or “specific.” The classification, as with anything, is situation dependent.

General-Specific Physical Preparation refers to exercises or drills which are close to sporting form, but are far enough away that they do not fit the realm of general. This would include things like pushing a heavy weighted sled for short distances for a football lineman.

Specific Physical Preparation refers, essentially, to sport practice, or the practice of any skill specific to your sport(s).

It should also be noted that, if you are not a competitive athlete, EVERYTHING is GPP for you! No matter how you classify yourself, if you are not competing, everything you do is general.

(A quick aside: where the exercises are practiced has no bearing on their classification. For example, football players running miles during practice is GPP – it has no specificity to their sport. However, those same players doing conditioning work with something like a 5 second work time and 30 second recovery in a park somewhere during the summer would trend closer to G-SPP and SPP. Another example, using another sport might be various jumps for volleyball players. An approach jump, in which the athlete performs the steps just as they would in a game, is SPP. A standard vertical jump would be G-SPP or SPP, as it is similar to the sport skill as well. However, something like depth jumps (dropping off of a surface, then rebounding and jumping quickly onto another box) could possibly be qualified as GPP for a volleyball player, as little of their sport is truly plyometric.)

Dr. Yuri Verkhoshansky, a former Soviet coach and scientist, also known as the “father of plyometrics,” notes:

“Strength training (that includes prevalently the use of the overload exercises) was part of the training for the so-called speed strength sport events (weight lifting, throwing in track and field, etc.), in which the importance of this physical quality was clear. In other sport disciplines these exercises were used only as a means for General Physical Preparation.”

Going back to our previous discussion, in the power sports, these means may be classified as “general-specific” or “specific,” but in other sports, they are “general.” In any event, even coaches of other sports realized the importance of getting stronger! Any strength training that is not directly tied to your sport, is part of GPP. Also note that GPP is not just lifting weights; any type of training that is not specific to the sport falls under this umbrella.

Another issue with the idea of using Crossfit for athletes is that, according to their definition, all aspects of “fitness” are equally important. However, I think all of us would agree that the need for local muscular endurance for a football player will not be the same as it is for a swimmer. Conversely, the need for explosive power development at the hips will not be the same for a triathlete that it will be for a volleyball player. For this reason, particularly as athletes advance in their sport, the need for more focused work becomes of the utmost importance. While a football player may have a weak Fran time, it’s irrelevant, because it will have no bearing on their sporting ability.

They will, however tout their “generality” as a strong point of their training philosophy. However, we must remember that things like “pre-hab” & rehab exercises are part of GPP also, and the exercise selection used in the training of certain athletes will change based on both individual weaknesses and those caused by the specificity of their training. Many sports and athletes need the addition of a lot of upper back/rear delt work to counteract the heavy volumes of forward propulsion of the arm, whether throwing (football/baseball/etc.), swimming, or striking (volleyball/tennis/etc.). These repeated movements often result in excessive internal rotation at the shoulder and excess strain on the rotator cuff. Some sports may require specific knee or ankle proprioception work as part of their training. Many athletes need to learn proper body mechanics in things like running and landing before even progressing to more advanced versions. As you can see, the organization of a “GPP” program is not as simple as “do a bunch of stuff and get tired.”

We also know that the physical quality of strength positively impacts a number of other physical qualities, much more so than the other way around (i.e. training endurance has minimal to no effect on strength, but getting stronger will have at least some impact on endurance for various reasons). As Pavel says, “Strength is the mother quality. It should never go out of style.” This means that it is more important than other qualities (up to a certain point). Placing equal emphasis on all qualities results in a “jack of all trades, master of none.”

However, a few years ago, Dr. Verkhoshansky was discussing the use of resistance training for sportsmen on his forum. He was lamenting that it had taken him quite a while to convince coaches of sports outside the conventional “power” sports (weightlifting, sprints, throws) to use resistance training. Although, he was eventually able to change their minds, he noticed a different trend. The quote from Dr. Verkhoshansky:

“When, in the EAST Europe, the training with overload has become an essential element of the preparation for all sporting disciplines, the coaches have gone to the other extreme: the volume of these loads has become excessive. The problem was not in the excess of the strength level, but that the athletes were so busy in the work with weights that they didn’t have time to develop the capacity to express this strength in the competition exercise. The problem was not to find the best method to develop the maximal strength but to elaborate, for every sport disciplines, a system of training that allowed to assemble the strength loads with the other loads in a way to assure the improvement of sport result.”

While this quote is a bit difficult to decipher (English is not Dr. Verkhoshansky’s first language), he is saying that, while coaches have accepted the importance of resistance training in improving their athletes’ results, the coaches have gone so far in that direction, that this training is adversely affecting the sport results. As I have stated already, the purpose of GPP training is to improve sport performance! High volumes of general work, particularly performed at high intensities, do not necessarily accomplish this (*cough* Crossfit *cough*).

And although he is talking about this issue in Eastern Europe, the issue can be seen anywhere. Too much general training, particularly at higher levels, drags down performance. This is why it is important to consider ALL training (including sport practice) when programming general preparation for athletes.

Do No Harm

The #1 rule for any strength and conditioning coach, physical preparation coach, personal trainer, or whatever title you see fit to give yourself, is DO NO HARM. That is, to select and execute exercises and programs which will derive the greatest benefit with the least amount of risk of injury to the athlete, in both the short and long term. The goal is to make them injury resistant, not increase the likelihood of it happening. And if you have a look at the injury rates of Crossfit, you will see that it is quite alarming. Heck, just check this out.

Correct exercise execution is a requirement as well. With that in mind, performing highly skill-dependent lifts with any significant load under fatigued conditions is unwise.

For example, the Olympic lifts can cause undue strain on the joints of the shoulders, elbows, and wrists, as well as the low back and knees, if performed incorrectly (please note this is NOT specific to the Olympic lifts – any lift performed poorly greatly increases risk of injury). Which is a near certainty when they are performed in a fatigued state or when using high repetitions.

The same can be said of high-rep depth jumps, particularly when performed by those of low preparation and strength. Depth jumps, performed properly, are a form of plyometrics. However, a ground contact time of over 0.2 seconds moves the exercise out of the category of plyometrics, and changes the purpose of the exercise from “improving reactive ability” to “destroying your Achilles.”

What about younger athletes, you ask? The ones who do need to be training multiple physical qualities at the same time? Professor Vladimir Koprivica states that the first thing youth athletes should do is learn the “motor alphabet.” That is, how to move properly. Now, ideally this happens early, but many times that is not the case. And they certainly don’t need to be training them balls-out. The mindset of “keep them busy, get them tired” pervades this industry and our country as a whole, but it doesn’t mean it’s the optimal way to do things. Kids should absolutely move themselves in a variety of ways, work on kinesthetic awareness, and learn proper movement patterns. And that last one is crucial. Proper technique is always taught best in a non-fatigued state. This means doing endless repetitions while tired will only serve to ingrain crappy technique. As they say, “practice doesn't make perfect, perfect practice makes perfect.”

Additionally, the use of high-intensity activities resulting in high levels of lactic acid accumulation can have extremely adverse effects on youth athletes. A quote from James Smith:

“Higher intensity training that is either carried out for too long a duration (>8sec) and/or separated by recovery periods that are too short (i.e., gassers, suicides, 300yd shuttles…), and/or shorter duration intervals that are carried out for an extended series of repetitions without sufficient recoveries places too much stress on a pre-pubescent youth’s cardiovascular system. The associated training intensity yields a situation in which too much stress is placed upon the myocardium.Stereotypically, higher heart rate training intensities increase the thickness of the left ventricular wall while lower heart rate training intensities (higher in volume) stretch the tissues of the left ventricular wall. While the former adaptation is more closely associated with high power output sports and the latter more favorable for endurance sports, the former can, in the extreme, lead to premature thickening of the left ventricular wall and cardiac problems in youths who are not yet prepared for the associated training load intensity. In the extreme, one must logically question whether such loading may lead to hypertrophic cardiac myopathy- a potentially fatal condition. At the least, the transitional muscle fibers of youths, that have not yet assumed white or red characteristics, are much more likely to assume red qualities and limit that youth’s speed/power potential later in life.”

In other words, pre-pubescent kids need to be focused on alactic, aerobic work (which probably sounds like Mandarin at the moment, but I’ll clarify these terms now).

A-T-Wha?

Humans have 3 energy systems which provide energy for our muscles to contract. Each vary in terms of their potential output, as well as their availability.

- Alactic-anaerobic – Also called the ATP-PC system, ATP is what makes our muscles contract. Our muscles always have ATP in them, as well as creatine phosphate (the same creatine that you take if you ingest the supplement). This system is very powerful, and provides energy immediately, but fizzles quickly, and is usually done at about 10-12 seconds.

- Lactic Glycolysis – Lactic acid begins accumulating, and the body uses this for energy. However, this system also is responsible for the muscles shutting down if an activity of too high intensity is sustained for too long. This system is not as powerful as the first, and also is responsible for the “burn” you feel in the muscles. Lasts up to 2-3 minutes

- Aerobic Glycolysis – uses oxygen to produce energy. Lasts as long as we have fuel (glycogen and/or fat) to sustain it.

It is important to note that all 3 systems are always being used, simply in different amounts. For instance, you are always producing lactic acid; it just isn’t accumulating, because you’re not working hard enough to make it build up.

And while it might seem like the ATP-PC and aerobic systems have little effect on one another (because they’re so far apart), the aerobic system is quite important, especially in team sports! The better developed your aerobic system is, the more quickly ATP can be replenished, and the faster you can use that energy system again. Sounds like a recipe for success!

Interestingly, aerobic development and lactic acid development seem to be at odds with one another – shocker! High aerobic development produces greater mitochondrial density in the cells. Mitochondria are the “powerhouse” of the cell, where oxygen is processed and turned into ATP. More mitochondria = more ATP production. However, the frequent training with lactic acid loads destroys mitochondria, thereby dragging down aerobic capacity in the cells.

A snippet from an article by Eric Oetter sums this up much better than I:

“For the most part, the energy systems demands of a repeated-sprint athlete are alactic-aerobic. The alactic system is responsible for providing the immediate energy to drive high-intensity movement while the aerobic system serves as the foundation for substrate recovery between bouts of activity.…Simply following the ball (or discounting the huddle, in the case of American football) might mislead onlookers into overestimating the glycolytic demands of repeated-sprint sports. However, in light of the Osgnach study and time-motion research on other sports, it’s clear that the bulk of the metabolic demands lie in the other two energy systems.This begs the question – why, if these athletes rely so heavily on the alactic and aerobic systems, is there still overwhelming support of high-intensity, glycolytic-based training methods?One theory is that high-intensity seems to be the rule in training. The current American system thrives on running people into the ground – it’s primarily the athletes possessing genetic superiority that rise to the top levels of competition and get to play. While I’m not advocating an easy way out, research points to much smarter methods in preparing our athletes for sport.Overreliance on high-intensity techniques can produce undesirable ramifications for repeated-sprint athletes. For example, the constant sympathetic nervous system activation associated with this style of training can impair an athlete’s recovery between bouts of activity and between individual training sessions.And due to the competing adaptations present, a focus on glycolytic development ensures suboptimal aerobic development. Considering the aforementioned ATP-CP and medium-intensity demands of repeated-sprint athletes, inadequate preparation will lead them to dip into glycolysis sooner and cause them to fatigue faster.”

(For more on energy systems, and why the lactic energy system is the last thing that needs to be emphasized, read the rest of the article from 8weeksout.)

Anyone who is familiar with the foundation of Crossfit – the “metcon” – knows that these are definitely lactic events. High intensity, with little to no rest. But as we’ve seen, that’s about the last thing athletes need.

Wrapping Up

Crossfit appeals to many because of its “hardcore, balls-to-the-wall” attitude. Every workout is “great” because it leaves you dripping with sweat and lying on the floor. However, as I stated earlier, our “keep ‘em busy, get ‘em tired” philosophy, while popular, is far from optimal. Your state post-workout should not be the indicator as to the effectiveness of your training. Your results in your sport should. And when using that as a barometer, I see nowhere that the Crossfit ideology can possibly win out. Additionally, hyping its superiority due to the fact that it is GPP is, as we have seen, extremely misguided. Ask any athlete that has trained using a well-planned out, intelligently-designed program, and they will tell you it easily surpasses beating the piss out of themselves on a daily basis because they think that’s what they’re supposed to do. Remember – any idiot can make you tired, and most do; but it takes someone who actually knows what they’re doing to make you better.

Questions? Comments? Please fire away!

No comments:

Post a Comment